Distributional Regression for Motorcycle Crash Data with Time-Varying Location and Scale Parameters

Source:vignettes/distributional-regression.Rmd

distributional-regression.RmdIntroduction

Motorcycle crash dynamics involve complex patterns where both the

mean acceleration and its variability change dramatically over time

during impact events. Traditional Gaussian regression assumes constant

variance, potentially missing critical safety insights about periods of

extreme or unpredictable forces. This vignette demonstrates how

distributional regression with the ffc package

addresses these challenges through:

- Time-varying location parameters capturing evolving mean

acceleration patterns

- Time-varying scale parameters modeling heteroskedasticity during

impact phases

- Rolling forecast evaluation for robust model validation

- Comprehensive uncertainty quantification for safety applications

The crash dynamics challenge

Motorcycle crash acceleration data presents unique modeling challenges:

- Non-constant variance during different impact phases

- Complex temporal evolution of both mean and variability

- Need to predict both typical and extreme force scenarios

- Critical safety implications requiring proper uncertainty bounds

Our approach: distributional GAMs with functional coefficients

The ffc package treats both location and scale as smooth

functions that evolve over time. By combining mgcv

distributional families with functional regression, we can:

- Model time-varying mean acceleration trends

- Capture evolving variance patterns throughout crash sequences

- Generate probabilistic forecasts with parameter-specific

uncertainty

- Validate predictions using rolling forecast techniques

Data exploration

We’ll use the classic motorcycle crash dataset from MASS,

representing head acceleration measurements during simulated motorcycle

crashes:

data(mcycle, package = "MASS")

mcycle$index <- 1:NROW(mcycle)

# Check data structure

glimpse(mcycle)

#> Rows: 133

#> Columns: 3

#> $ times <dbl> 2.4, 2.6, 3.2, 3.6, 4.0, 6.2, 6.6, 6.8, 7.8, 8.2, 8.8, 8.8, 9.6,…

#> $ accel <dbl> 0.0, -1.3, -2.7, 0.0, -2.7, -2.7, -2.7, -1.3, -2.7, -2.7, -1.3, …

#> $ index <int> 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 1…Visualizing acceleration patterns

ggplot(mcycle, aes(x = index, y = accel)) +

geom_point(alpha = 0.7, size = 2) +

geom_line() +

geom_vline(xintercept = 110, linetype = "dashed", color = "darkred", alpha = 0.7) +

labs(

x = "Time Index",

y = "Head Acceleration",

title = "Motorcycle crash data: heteroskedastic acceleration patterns"

)

Head acceleration measurements showing clear heteroskedasticity over time.

The data shows low variance before impact, extreme variance during the crash, and moderate variance in the rebound phase.

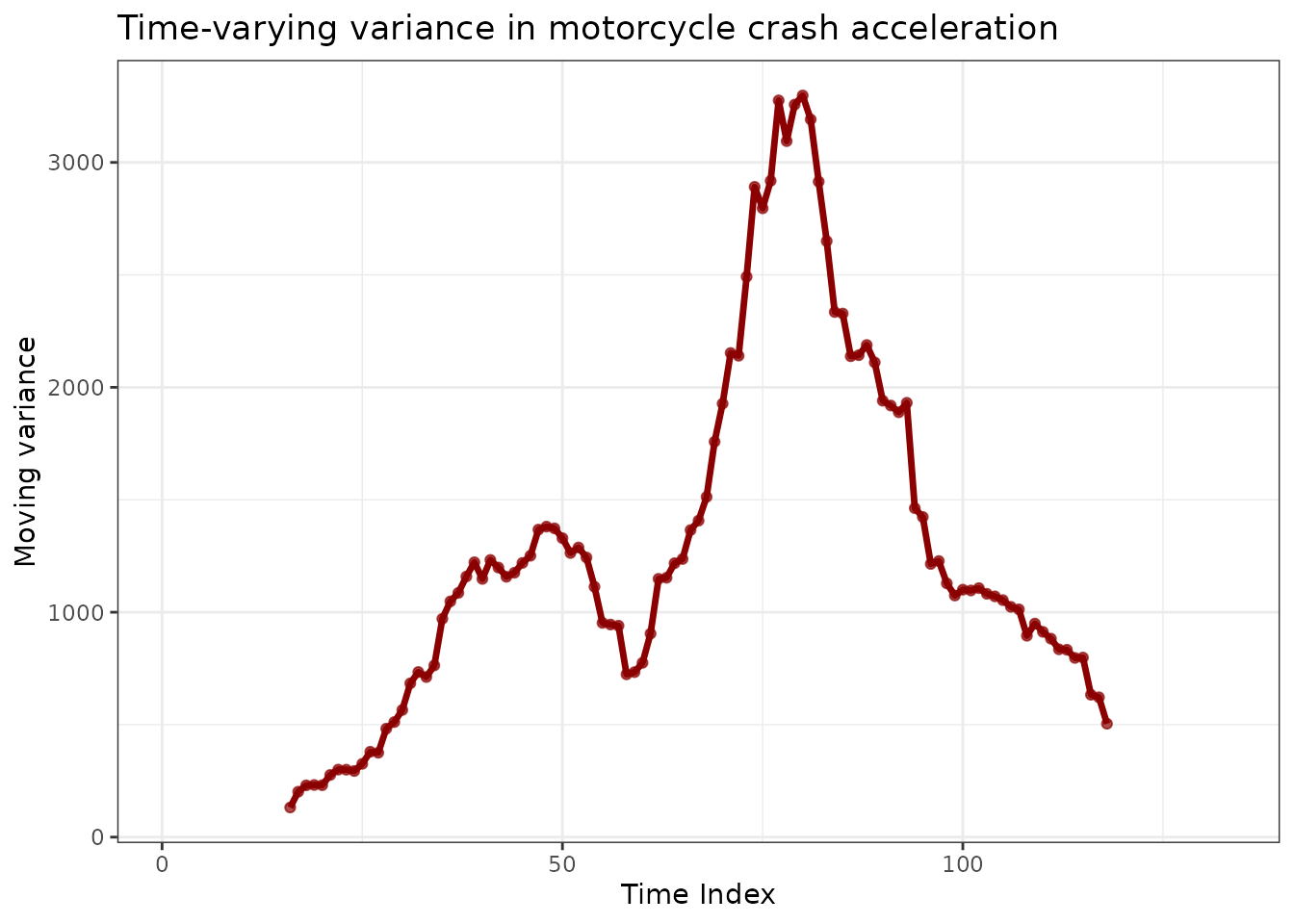

Identifying variance patterns

Let’s examine how variance changes across different phases of the crash sequence:

# Calculate moving variance with overlapping windows

window_size <- 15

mcycle$moving_var <- NA

for (i in (window_size + 1):(nrow(mcycle) - window_size)) {

window_data <- mcycle$accel[(i - window_size):(i + window_size)]

mcycle$moving_var[i] <- var(window_data, na.rm = TRUE)

}

ggplot(mcycle, aes(x = index)) +

geom_line(aes(y = moving_var), color = "darkred", linewidth = 1.2) +

geom_point(aes(y = moving_var), color = "darkred", alpha = 0.7) +

labs(

x = "Time Index",

y = "Moving variance",

title = "Time-varying variance in motorcycle crash acceleration"

)

Moving variance reveals dramatic changes in acceleration variability over time.

The moving variance peaks dramatically during the crash phase, confirming that constant variance assumptions would be inappropriate for this data.

Modeling with distributional GAMs

Train-test split for validation

We’ll use early crash data for training and reserve later impact phases for validation:

The distributional model specification

Now let’s fit a model that will allow us to forecast changes in both

the mean and the variance. The key innovation is using gaulss()

to model both location and scale parameters with functional time

series:

Understanding the model structure

summary(mcycle_gaulss_model)

#>

#> Family: gaulss

#> Link function: identity logb

#>

#> Formula:

#> accel ~ s(index, by = location_fts_index1_mean, bs = "ts", k = 25,

#> m = 2)

#> ~s(index, by = scale_fts_index1_mean, bs = "ts", k = 25, m = 2)

#>

#> Parametric coefficients:

#> Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

#> (Intercept) -31.14284 2.18787 -14.23 <2e-16 ***

#> (Intercept).1 2.55943 0.07069 36.21 <2e-16 ***

#> ---

#> Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

#>

#> Approximate significance of smooth terms:

#> edf Ref.df Chi.sq p-value

#> s(index):location_fts_index1_mean 10.440 24 627.4 <2e-16 ***

#> s.1(index):scale_fts_index1_mean 4.334 24 282.8 <2e-16 ***

#> ---

#> Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

#>

#> Deviance explained = 99.3%

#> -REML = 476.13 Scale est. = 1 n = 109The model decomposes crash dynamics into:

-

Location parameter: Smooth time-varying mean

acceleration

- Scale parameter: Time-varying standard deviation modeling heteroskedasticity

The gaulss()

family uses log-link for the scale parameter, ensuring positive variance

estimates throughout the crash sequence.

Model diagnostics and interpretation

Visualizing fitted trends and variance

We can examine how the model captures both mean trends and changing variance:

# Extract time-varying coefficients for both parameters

fts_results <- fts_coefs(mcycle_gaulss_model, summary = FALSE)

autoplot(fts_results) +

labs(

title = "Time-varying distributional parameters",

x = "Time Index",

y = "Coefficient Value"

)

Fitted location and scale parameters reveal distinct temporal patterns in crash dynamics.

The location parameter captures the mean acceleration trajectory while the scale parameter adapts to varying uncertainty levels throughout the crash sequence.

Extracting parameter-specific coefficients

The functional coefficients reveal the underlying dynamics of each distributional parameter:

# View coefficient structure

fts_results

#> # A tibble: 5,450 × 6

#> .basis .parameter .time .estimate .realisation index

#> * <chr> <chr> <int> <dbl> <int> <int>

#> 1 location_fts_index1_mean location 1 27.8 1 1

#> 2 location_fts_index1_mean location 2 27.2 1 2

#> 3 location_fts_index1_mean location 3 26.7 1 3

#> 4 location_fts_index1_mean location 4 26.3 1 4

#> 5 location_fts_index1_mean location 5 26.2 1 5

#> 6 location_fts_index1_mean location 6 26.2 1 6

#> 7 location_fts_index1_mean location 7 26.1 1 7

#> 8 location_fts_index1_mean location 8 26.0 1 8

#> 9 location_fts_index1_mean location 9 25.8 1 9

#> 10 location_fts_index1_mean location 10 25.4 1 10

#> # ℹ 5,440 more rows

# Summary statistics by parameter

fts_results |>

as_tibble() |>

group_by(.parameter, .basis) |>

summarise(

mean_coef = mean(.estimate),

sd_coef = sd(.estimate),

.groups = "drop"

)

#> # A tibble: 2 × 4

#> .parameter .basis mean_coef sd_coef

#> <chr> <chr> <dbl> <dbl>

#> 1 location location_fts_index1_mean -2.02e-12 44.9

#> 2 scale scale_fts_index1_mean 5.22e-15 1.17Forecasting distributional models

Single forecast demonstration

Generate forecasts that provide both mean predictions and uncertainty intervals based on the evolving variance structure:

fc_single <- forecast(

mcycle_gaulss_model,

newdata = mcycle_test,

model = "ENS",

mean_model = "ENS"

)

# Examine forecast structure

fc_single

#> # A tibble: 24 × 6

#> .estimate .error .q2.5 .q10 .q90 .q97.5

#> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

#> 1 16.2 26.0 -52.8 -28.1 69.5 94.0

#> 2 26.4 28.3 -59.2 -29.9 78.8 120.

#> 3 17.8 36.2 -110. -45.4 86.8 132.

#> 4 35.7 29.7 -59.5 -15.3 103. 126.

#> 5 17.6 30.9 -52.0 -28.2 78.7 113.

#> 6 7.02 33.6 -63.9 -43.0 72.3 125.

#> 7 15.3 34.9 -112. -50.1 94.5 119.

#> 8 5.44 30.4 -96.6 -52.9 71.3 102.

#> 9 17.5 24.4 -61.0 -31.5 64.2 94.5

#> 10 21.4 28.6 -104. -42.8 64.4 115.

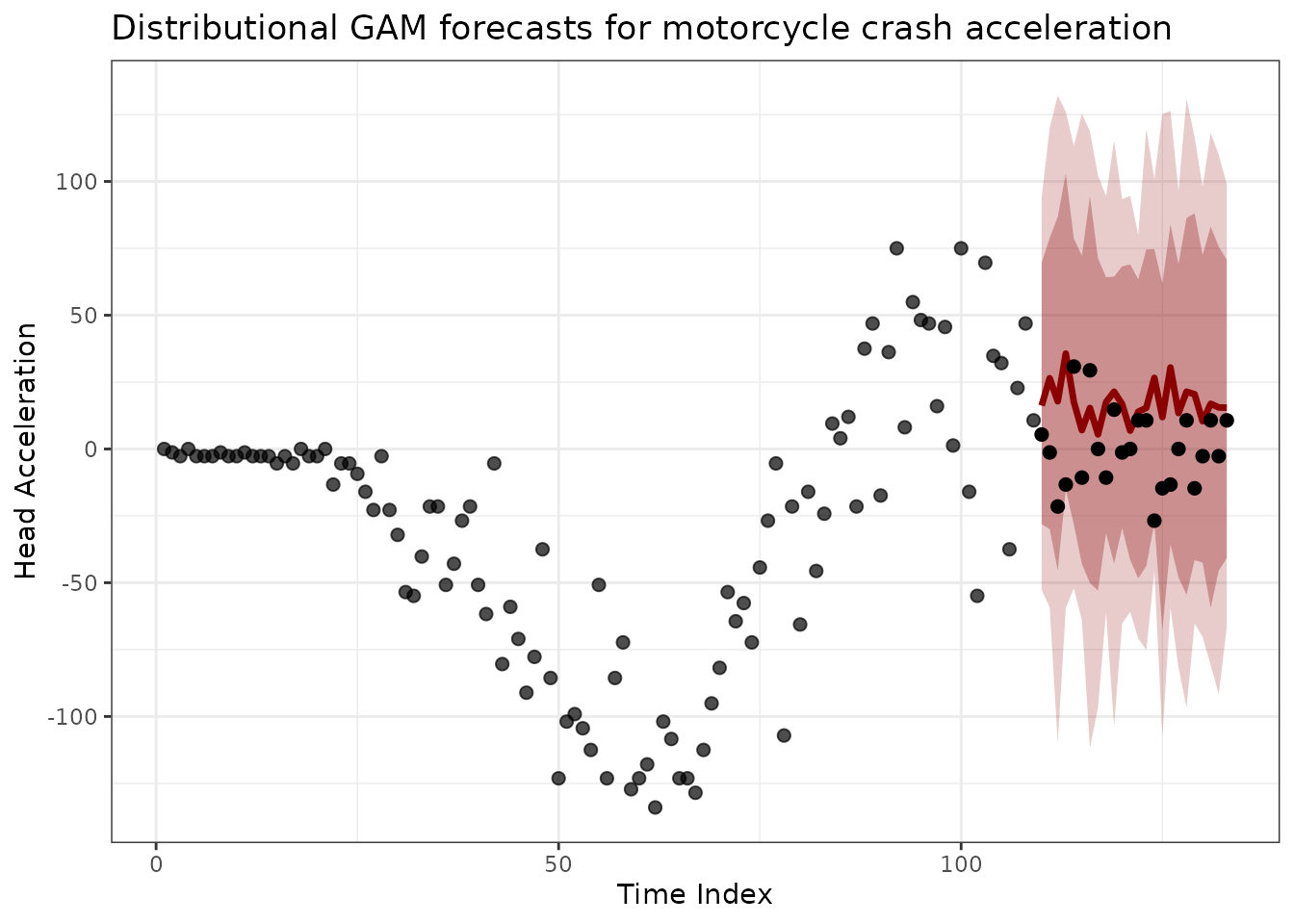

#> # ℹ 14 more rowsVisualizing distributional forecasts

# Combine training and forecast data for visualization

forecast_plot_data <- mcycle_train |>

as_tibble() |>

mutate(type = "observed") |>

bind_rows(

mcycle_test |>

as_tibble() |>

bind_cols(fc_single) |>

mutate(type = "forecast")

)

ggplot(forecast_plot_data, aes(x = index, y = accel)) +

geom_point(data = filter(forecast_plot_data, type == "observed"),

alpha = 0.7, size = 2) +

geom_ribbon(data = filter(forecast_plot_data, type == "forecast"),

aes(ymin = .q2.5, ymax = .q97.5),

fill = "darkred", alpha = 0.2) +

geom_ribbon(data = filter(forecast_plot_data, type == "forecast"),

aes(ymin = .q10, ymax = .q90),

fill = "darkred", alpha = 0.3) +

geom_line(data = filter(forecast_plot_data, type == "forecast"),

aes(y = .estimate),

colour = "darkred", linewidth = 1.2) +

geom_point(data = filter(forecast_plot_data, type == "forecast"),

color = "black", size = 2) +

labs(

title = "Distributional GAM forecasts for motorcycle crash acceleration",

x = "Time Index",

y = "Head Acceleration"

)

Distributional forecasts capture both mean trends and evolving uncertainty from the time-varying scale parameter.

The widening prediction intervals in the test period reflect increasing uncertainty as we forecast further from the training data, a natural consequence of parameter extrapolation.

Coefficient forecast inspection

We can also forecast the functional coefficients themselves to understand how the underlying parameters evolve:

# Forecast the coefficients to the test period

coef_forecast_raw <- forecast(

fts_results,

h = nrow(mcycle_test),

model = "ENS"

)

# Summarize coefficient forecasts

coef_forecast <- coef_forecast_raw |>

as_tibble() |>

group_by(.basis, .time) |>

summarise(

.estimate = mean(.sim),

.q2.5 = quantile(.sim, 0.025),

.q97.5 = quantile(.sim, 0.975),

.groups = "drop"

)

# Summarize training coefficients

fts_coefs_summary <- fts_results |>

as_tibble() |>

group_by(.basis, .time) |>

summarise(

.estimate = mean(.estimate),

.groups = "drop"

)

# Visualize coefficient evolution and forecasts

ggplot() +

geom_line(data = fts_coefs_summary,

aes(x = .time, y = .estimate, color = .basis),

linewidth = 1) +

geom_ribbon(data = coef_forecast,

aes(x = .time, ymin = .q2.5, ymax = .q97.5, fill = .basis),

alpha = 0.2) +

geom_line(data = coef_forecast,

aes(x = .time, y = .estimate, color = .basis),

linewidth = 1.2) +

facet_wrap(~ .basis, scales = "free_y") +

labs(

title = "Functional coefficients: training vs forecasted",

x = "Time Index",

y = "Coefficient Value"

) +

theme(legend.position = "none")

Forecasted functional coefficients show parameter-specific evolution patterns with quantified uncertainty.

The forecasts for both parameters reflect the underlying nonlinear dynamics captured by the exponential smoothing and random walk ensemble model.

Rolling forecast evaluation

Understanding rolling forecast evaluation

Rolling forecast evaluation, also known as time series cross-validation, provides a more robust assessment of model performance than traditional train-test splits. Instead of evaluating predictions from a single time point, this approach tests how well a model performs when making forecasts from many different origins throughout the time series. This mimics real-world forecasting scenarios where we continuously update our models with new data and generate fresh predictions.

The method works by sliding a fixed-size training window through the time series. At each position, we fit the model using only the data within that window, then generate forecasts for a specified number of steps ahead (the forecast horizon). By advancing the window position systematically (determined by the step size), we obtain multiple sets of forecasts that can be evaluated against the actual observed values. This reveals whether our model maintains consistent performance across different time periods and data conditions.

For distributional models like ours, rolling evaluation is particularly valuable because it tests whether prediction intervals remain well-calibrated throughout the entire time series. In safety-critical applications such as crash analysis, we need confidence that our uncertainty estimates are reliable not just on average, but consistently across all phases of the crash timeline.

Rolling forecast parameters

# Use 70 observations for each training window - enough data to estimate

# time-varying parameters while allowing multiple forecast origins

window_size <- 70

# Predict 5 steps ahead from each origin - tests short-term accuracy

# relevant for crash dynamics without extending into highly uncertain territory

forecast_horizon <- 5

# Advance forecast origin by 5 steps between evaluations - balances

# computational cost with evaluation thoroughness

step_size <- 5

# Calculate where each forecast origin will be positioned

max_start <- nrow(mcycle) - forecast_horizon

forecast_starts <- seq(1, max(1, max_start - window_size), by = step_size)The choice of window size reflects a trade-off between having enough data to reliably estimate model parameters and maintaining enough forecast origins for robust evaluation. Our window of 50 observations captures sufficient crash dynamics while the step size of 10 provides reasonable coverage of the timeline without excessive computational burden. The 10-step forecast horizon tests the model’s ability to predict the immediate future, which is most relevant for understanding crash dynamics where conditions can change rapidly.

Executing rolling forecasts

The rolling forecast loop systematically moves through the time series, fitting a fresh model at each origin and generating predictions for the subsequent time points. This process simulates how forecasting works in practice, where we periodically retrain our models with the latest available data.

# List to accumulate results from each forecast origin

rolling_results <- list()

# Loop through each forecast origin position

for (i in seq_along(forecast_starts)) {

# Define the training window boundaries

start_idx <- forecast_starts[i]

end_idx <- min(start_idx + window_size - 1, nrow(mcycle))

# Extract training data for this window

train_data <- mcycle[start_idx:end_idx, ]

# Define the test period immediately following the training window

test_start <- end_idx + 1

test_end <- min(test_start + forecast_horizon - 1, nrow(mcycle))

# Only proceed if we have enough data for the full test period

if (test_end <= nrow(mcycle)) {

test_data <- mcycle[test_start:test_end, ]

# Fit a distributional model to the training window

# Using mean_only = TRUE for computational efficiency in the loop

roll_model <- ffc_gam(

list(

accel ~ fts(index, mean_only = TRUE, time_k = 10),

~ fts(index, mean_only = TRUE, time_k = 10)

),

family = gaulss(),

data = train_data,

time = "index"

)

# Generate forecasts for the test period using ensemble method

roll_forecast <- forecast(

roll_model,

newdata = test_data,

model = "ENS"

)

# Combine actual values with predictions and add tracking metadata

rolling_results[[i]] <- test_data |>

bind_cols(roll_forecast) |>

mutate(

forecast_origin = i,

train_start = start_idx,

train_end = end_idx,

horizon = 1:nrow(test_data)

)

}

}

# Combine all forecast results into a single data frame for analysis

rolling_forecasts <- bind_rows(rolling_results)Each iteration of this loop represents a realistic forecasting scenario where we have historical data up to a certain point (the training window) and must predict what happens next. The metadata we track allows us to analyze how performance varies by forecast origin and horizon.

Rolling forecast performance analysis

Forecast accuracy metrics

To evaluate our distributional forecasts comprehensively, we calculate both point forecast accuracy measures and coverage statistics for the prediction intervals. Coverage refers to the proportion of actual observations that fall within the predicted intervals. A well-calibrated 95% prediction interval should contain the true value approximately 95% of the time across many forecasts. If coverage is substantially lower, the model is overconfident; if higher, it is being unnecessarily conservative.

# Calculate comprehensive performance metrics for each forecast

rolling_forecasts <- rolling_forecasts |>

mutate(

# Point forecast errors

forecast_error = accel - .estimate,

abs_error = abs(forecast_error),

squared_error = forecast_error^2,

# Coverage indicators: TRUE if actual value falls within interval

coverage_95 = (accel >= .q2.5) & (accel <= .q97.5),

coverage_80 = (accel >= .q10) & (accel <= .q90),

# Interval widths to assess uncertainty magnitude

interval_width_95 = .q97.5 - .q2.5,

interval_width_80 = .q90 - .q10

)

# Performance by forecast horizon

horizon_stats <- rolling_forecasts |>

group_by(horizon) |>

summarise(

n_forecasts = n(),

mae = mean(abs_error, na.rm = TRUE),

rmse = sqrt(mean(squared_error, na.rm = TRUE)),

coverage_95 = mean(coverage_95, na.rm = TRUE),

coverage_80 = mean(coverage_80, na.rm = TRUE),

avg_width_95 = mean(interval_width_95, na.rm = TRUE),

avg_width_80 = mean(interval_width_80, na.rm = TRUE),

.groups = 'drop'

)

horizon_stats

#> # A tibble: 5 × 8

#> horizon n_forecasts mae rmse coverage_95 coverage_80 avg_width_95

#> <int> <int> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

#> 1 1 12 27.0 35.3 0.833 0.667 114.

#> 2 2 12 31.6 41.5 0.75 0.667 112.

#> 3 3 12 26.0 32.4 0.833 0.833 114.

#> 4 4 12 27.4 31.1 1 0.75 122.

#> 5 5 12 23.0 29.6 0.917 0.833 122.

#> # ℹ 1 more variable: avg_width_80 <dbl>

# Overall performance summary

overall_stats <- rolling_forecasts |>

summarise(

total_forecasts = n(),

overall_mae = mean(abs_error, na.rm = TRUE),

overall_rmse = sqrt(mean(squared_error, na.rm = TRUE)),

overall_coverage_95 = mean(coverage_95, na.rm = TRUE),

overall_coverage_80 = mean(coverage_80, na.rm = TRUE)

)

cat("- 95% coverage:", round(overall_stats$overall_coverage_95 * 100, 1), "%\n")

#> - 95% coverage: 86.7 %

cat("- 80% coverage:", round(overall_stats$overall_coverage_80 * 100, 1), "%\n")

#> - 80% coverage: 75 %Rolling forecast visualization

# Visualize rolling forecasts over the full time series

ggplot() +

geom_point(data = mcycle, aes(x = index, y = accel),

alpha = 0.4, size = 1) +

geom_line(data = mcycle, aes(x = index, y = accel),

alpha = 0.4) +

geom_point(data = rolling_forecasts,

aes(x = index, y = .estimate),

color = "darkred", size = 1.5, alpha = 0.8) +

geom_errorbar(data = rolling_forecasts,

aes(x = index, ymin = .q10, ymax = .q90),

color = "darkred", alpha = 0.6, width = 0.5) +

geom_segment(data = rolling_forecasts,

aes(x = index, xend = index, y = accel, yend = .estimate),

color = "darkblue", alpha = 0.3, linetype = "dashed") +

labs(

title = "Rolling forecast evaluation across crash timeline",

x = "Time Index",

y = "Head Acceleration"

)

Rolling forecast evaluation reveals consistent prediction performance across different crash phases.

The plot shows forecasts (red points) with 80% prediction intervals capturing the observed values across diverse crash phases, demonstrating consistent model performance.

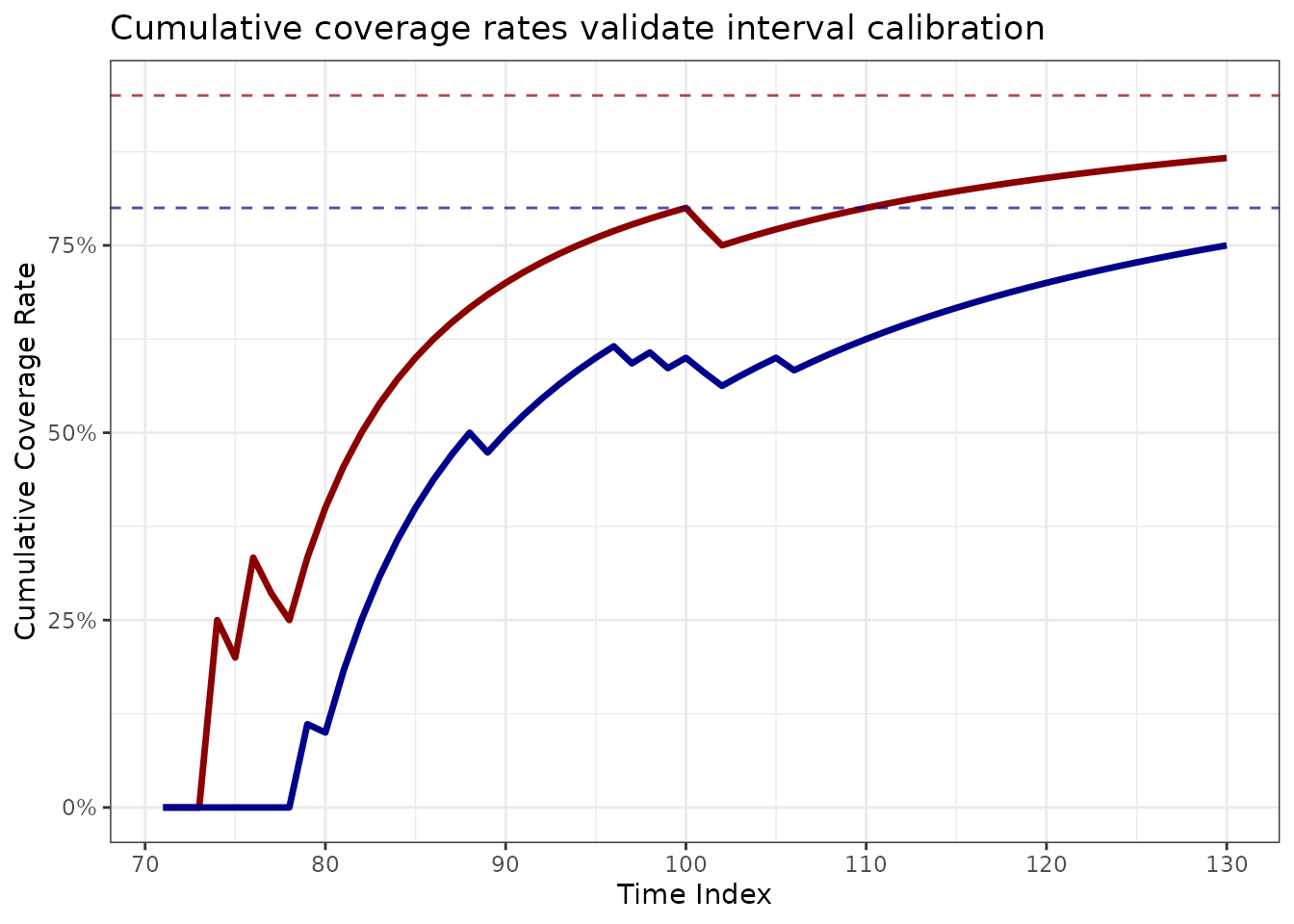

Coverage evolution analysis

# Track coverage evolution over evaluation period

coverage_data <- rolling_forecasts |>

arrange(index) |>

mutate(

running_coverage_95 = cumsum(coverage_95) / row_number(),

running_coverage_80 = cumsum(coverage_80) / row_number()

)

ggplot(coverage_data, aes(x = index)) +

geom_line(aes(y = running_coverage_95), color = "darkred", linewidth = 1.2) +

geom_line(aes(y = running_coverage_80), color = "darkblue", linewidth = 1.2) +

geom_hline(yintercept = 0.95, linetype = "dashed", color = "darkred", alpha = 0.7) +

geom_hline(yintercept = 0.80, linetype = "dashed", color = "darkblue", alpha = 0.7) +

scale_y_continuous(labels = scales::percent_format()) +

labs(

title = "Cumulative coverage rates validate interval calibration",

x = "Time Index",

y = "Cumulative Coverage Rate"

)

Cumulative coverage rates demonstrate improved coverage of prediction intervals throughout the evaluation.

The cumulative coverage rates fluctuate across the time index, revealing how the forecasts did not anticipate the initial, major rise in both acceleration and the variance. Once the models had seen that period, the forecasts improved substantially.

Key insights and best practices

When to use distributional regression

Distributional regression with ffc is essential

when:

- Data exhibits clear heteroskedasticity (changing variance over

time)

- Both mean trends and uncertainty evolution matter for

interpretation

- Risk assessment requires proper uncertainty bounds

- Traditional constant-variance assumptions are violated

Key implementation considerations:

Distributional forecasting advantages

The time-varying distributional approach excels when:

- Traditional homoskedastic models miss variance patterns

- Parameter-specific uncertainty quantification is needed

- Rolling validation reveals model robustness across conditions

- Safety applications require conservative interval estimation

For detailed guidance on distributional families in mgcv,

see Wood

(2017).

Conclusion

This vignette demonstrated advanced distributional regression techniques for motorcycle crash data:

- Time-varying location and scale parameters capture evolving crash

dynamics

- Functional time series coefficients provide interpretable parameter

evolution

- Rolling forecast evaluation ensures robust model validation

- Proper uncertainty quantification enables safety-critical applications

The ffc package integrates distributional modeling

seamlessly with functional forecasting: - List formula syntax for

multi-parameter specifications

- Parameter-specific coefficient extraction and forecasting

- Comprehensive validation through rolling forecast techniques

- Integration with mgcv

distributional families

Further reading

- Wood (2017): Generalized

Additive Models: An Introduction with R

- Rigby & Stasinopoulos (2005): Generalized

additive models for location, scale and shape

- Hyndman & Athanasopoulos (2021): Forecasting: Principles and

Practice

- mgcv distributional families documentation